|

| Tannhaäuser runs through March 6 at Lyric Opera of Chicago |

This series of posts presents an abbreviated version of lectures that I gave on Richard Wagner's Tannhäuser at the Lyric Opera of Chicago (August 7, 2014) and the Wagner Society of America (January 28, 2015). I have removed all discussion of musical elements, as it makes little sense without audio excerpts. Instead, this series focuses on the roots of Wagner’s Tannhäuser libretto in myth, legend, literature and history.

The Lyric Opera of Chicago is currently presenting a production of the opera that runs February 9 through March 15. If you can’t make it to Chicago but would like to hear the music, I recommend the 1971 recording by Georg Solti with the Vienna Philharmonic. The final installment of this series at The Norse Mythology Blog will include a bibliography of sources used – a list which can also serve as a guide for further reading.

|

| 1844 daguerreotype of Richard Wagner |

In order to understand the nature of Wagner’s magic mountain, we must turn to the scholarship of his time. Wagner writes in his autobiography that, in 1843 – the year he finished the poem then titled Der Venusberg – he was inseparable from his copy of Jacob Grimm’s Teutonic Mythology. First published in 1835, Grimm’s attempt to bring the scattered bits of Germanic heathen lore together into a coherent system had an outsized impact on Wagner, who wrote:

Formed from the scanty fragments of a perished world, of which scarcely any monuments remained recognizable and intact, I here found a heterogeneous building, which at first glance seemed but a rugged rock clothed in straggling brambles. Nothing was finished, only here and there could the slightest resemblance to an architectonic line be traced, so that I often felt tempted to relinquish the thankless task of trying to build from such materials. And yet I was enchained by a wondrous magic.

The baldest legend spoke to me of its ancient home, and soon my whole imagination thrilled with images; long-lost forms for which I had sought so eagerly shaped themselves ever more and more clearly into realities that lived again. There rose up soon before my mind a whole world of figures, which revealed themselves as so strangely plastic and primitive, that, when I saw them clearly before me and heard their voices in my heart, I could not account for the almost tangible familiarity and assurance of their demeanor.

The effect they produced upon the inner state of my soul I can only describe as an entire rebirth. Just as we feel a tender joy over a child's first bright smile of recognition, so now my own eyes flashed with rapture as I saw a world, revealed, as it were, by miracle, in which I had hitherto moved blindly as the babe in its mother's womb.Wagner relied heavily on Grimm while writing The Ring of the Nibelung, and Grimm’s idiosyncratic combination of philology, folklore, literature and legend can help to explain the mythological elements of Tannhäuser, as well.

|

| The Hörselberg in Germany |

Grimm writes that the Hörselberg of Thuringia was still considered in the 10th through 14th centuries to be the residence of the German goddess Holda and her host. He cites legends of “night-women in the service of dame Holda” who “rove through the air on appointed nights, mounted on beasts,” and asserts that they “were originally dæmonic elvish beings, who appeared in woman’s shape and did men kindnesses.”

During the orgiastic Bacchanale that follows the overture, Wagner presents us with naiads, nymphs, satyrs, fauns and other creatures of Greco-Roman mythology. Why would a composer as nationalistic as Wagner have replaced the native figures of German legend with their southern counterparts? The answer lies in the two characters portrayed in the opera’s first scene.

The historical Tannhäuser was a Minnesinger – a composer and performer of songs dealing with courtly love. There are many conflicting theories about his life, some of them quite fanciful. However, in the words of J.W. Thomas, “Nothing is known of the life of the thirteenth-century poet and composer Tannhäuser except for what can be learned from the relatively few lines of verse which have been ascribed to him by medieval anthologists.”

|

| "Der Tanhuser" from the Codex Manesse (Early 14thC) |

Seventeen poems survive. In four of them, the poet calls himself “tanhusere.” The name may mean “the one from Tannhausen,” and there are several places with this name. It may also mean “the backwoodsman” or “forest-dweller,” an apt nickname for a poet whose works are marked by ironic humor that pokes fun at the conventions of courtly society. The language used in the poems suggests that Tannhäuser was originally from Austria or Southern Germany, but attempts to place him more specifically are mostly speculative. He probably died sometime shortly after 1266.

What makes the poems by Tannhäuser so interesting is their irreverence for the accepted mores of Minnesong. Everything expected is set on its head. Other Minnesingers compose odes to unattainable courtly ladies; Tannhäuser writes celebrations of successfully bedding rustic women. Not bedding, exactly, since his conquests take place out-of-doors. Where other poets sing of the delicate features of their beloved and steer well clear of impropriety, Tannhäuser famously sings the praises of every part of his beloved-of-the-moment – including the bits under her skirt. His work is not pornographic or leering; everything is done with a knowing wink and an obvious delight in subverting the expectations of his listeners. It is this “joyous challenge” that Wagner portrays in his overture.

|

| Nadja Michael as Venus in Deutsche Oper Berlin's Tannhäuser (2008) |

Like the figures of the Bacchanale, Venus is imported from Greco-Roman mythology into a German setting. This is not a new idea of Wagner’s. As far back as the writings of Julius Caesar in the first century BCE, Romans were making the interpretatio romana – interpreting the native gods of the Germanic tribes they encountered in terms of their own pantheon. In the first century CE, the Roman writer Tacitus famously wrote that Germans worshiped Mercury, Hercules and Mars – figures that later scholars consider to be equivalent to Odin, Thor and Tyr.

The northern tribes made their own interpretatio germanica – relating the foreign gods of the invading Romans to their own deities. The most famous example of this – and one that survives in modern English – is the Germanization of the Roman weekday names. Mars’ day became Tyr’s day (Tuesday), Mercury’s day became Woden’s day (Wednesday), Jupiter’s day became Thor’s day (Thursday), and Venus’s day became Frigg’s day (Friday).

Wagnerians know Frigg as Fricka, the consort of Wotan. However, the attributes of Venus line up more clearly with the goddess Freya than they do with Frigg. Since at least the early 1900s, scholars have argued for an original identity for Frigg and Freya that – at some unknown point – split a complex female goddess into a mother figure and a maiden figure, into a goddess whose domain includes marriage and another associated with sexual love.

It is Freya’s characteristics that most closely conform to Wagner’s Venus. The Icelander Snorri Sturluson tells us in his 13th-century Edda that Freya “was very fond of love songs. It is good to pray to her concerning love affairs.” Indeed, it is Tannhäuser’s song in the overture that summons her. In the second scene, her first attempt at holding onto Tannhäuser is to tell him: “Come, my minstrel, up and grasp your lyre! Celebrate love, which you extol so marvelously in song, that you won the goddess of love herself for yours! Celebrate love, for its highest prize has become yours!”

|

| Wagner's Freia by Arthur Rackham (1910) |

In a discussion of the Venusberg legend, Grimm asserts that the identity of Venus with the German goddess Holda in these tales “is placed beyond question.” Wagnerians with a good ear for detail will remember that, in Das Rheingold, Freia is also referred to as Holde. By the transitive property, if Venus equals Holde and Holde equals Freya, Venus equals Freya.

If you are familiar with Norse mythology and are unhappy with the portrayal of Freya as a weepy teenager in The Ring – a characterization that owes more to Wagner’s impression of the fifteen-year-old Marie von Sayn-Wittgenstein than it does to the myths – here in Tannhäuser you can have a more powerful Wagnerian image of the northern goddess.

The direct lineal ancestor of the Venusberg legend is most likely the Italian folk legend, recorded by the French Antoine de la Sale around 1440, of an anonymous German knight who enters the Monte della Sibina (the Mountain of the Sibyl) in the Apennines and finds a sensual paradise within. After three hundred and thirty days of debauchery with the Sibyl and her retinue, he departs for Rome to confess his sins. The pope is sympathetic but publicly admonishes him and casts him out as an example to others. When the pontiff regrets his actions and sends for the knight, he finds that the German has decided to go back into the mountain.

For a story like this to have moved up from Italy to Germany, there were necessarily elements in the legend that struck a sympathetic chord for the new audience. The papal issue will be addressed later; the identification by the Germans of Venus with their own native goddesses should already be clear.

In his essay on the overture, Wagner describes the “drunken glee” of the Bacchantes: “a scurry, like the sound of the Wild Hunt, and speedily the storm is laid.” He thus links the orgy inspired by the Roman Bacchus to the tradition of spirits following Holda or Wotan’s flight through winter skies – a legend he returns to in The Ring of the Nibelungen.

|

| The Bacchanale by Willy Pogany (1911) |

After the overture and Baccahanale have run their course, Wagner gives us a hint that what we see is not what he is truly giving us – that we are not really watching an opera about nymphs and Nereids, but one about psychology and philosophy. The stage directions tell us that Tannhäuser lifts his head, “as if starting from a dream.” When Venus asks after his thoughts, he laments, “O, that I might now awake!” In Act 2, he will speak of his sojourn in the Venusberg in terms reminiscent of dreams: “Deep forgetfulness has descended betwixt today and yesterday. All my remembrance has vanished in a trice” – the time spent inside the mountain is the dream between his past and present life in the world. What is this dream – this illusion – within which Tannhäuser is trapped?

In A Communication to My Friends (1851), Wagner explains that behind his writing of Tannhäuser was his personal experience of “a conflict peculiar to our modern evolution.” The financial security and relative comfort of his appointment as Royal Kapellmeister in Dresden had led him away from his artistic ideals and goals. He writes:

Through the happy change in the aspect of my outward lot; through the hopes I cherished, of its even still more favorable development in the future; and finally through my personal and, in a sense, intoxicating contact with a new and well-inclined surrounding, a passion for enjoyment had sprung up within me, that led my inner nature, formed amid the struggles and impressions of a painful past, astray from its own peculiar path.

A general instinct that urges every man to take life as he finds it, now pointed me, in my particular relations as Artist, to a path which, on the other hand, must soon and bitterly disgust me. This instinct could only have been appeased in Life on condition of my seeking, as artist, to wrest myself renown and pleasure by a complete subordination of my true nature to the demands of the public taste in Art.

|

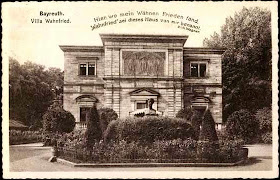

| Vintage postcard of Wagner's Wahnfried at Bayreuth |

This internal conflict between worldly pleasure and intellectual striving continued throughout Wagner’s life. In 1874, he named his Bayreuth villa Wahnfried (“peace from illusion”), a name that was, according to Derek Watson, “intended to symbolize his having at last found refuge from the outer world.” The illusion from which Wagner sought respite late in life is the “passion for enjoyment,” the waking dream of pleasure in which we first find Tannhäuser. The Venusberg, Wagner later wrote, is the “realm of non-being.” We’ll leave aside for the moment that “non-being” is exactly the goal of Wagner’s later version of Schopenhauerian Buddhism.

Watching the opera, we witness a dream within a dream. Wagner’s philosophical ideas are presented to us in the guise of history and legend. In his Communication, he writes of the power of folk poetry and myth to present truths that history cannot. He asserts that the folk poem

ever seizes on the kernel of the matter, and brings it again to show in simple plastic outlines; whilst there, in the history – i.e. the event not such as it was, but such alone as it comes within our ken – this matter shows itself in endless trickery of outer facings, and never attains that fine plasticity of form until the eye of the Folk has plunged into its inner soul, and given it the artistic mold of Myth.Wagner’s interweaving of mythologies with his own philosophies can be found throughout the opera. Tannhäuser, wakened (or not) from his dream of the Venusberg, says: “In dreams, it was as if I heard – a sound long stranger to my ears – as if I heard the joyful peal of bells!” Tannhäuser’s determination to leave the Venusberg begins with this dream-sound, leading Ernest Newman to write of the disastrous Paris performances: “The average Parisian could not understand how the mere sound of a bell could tear Tannhäuser out of the arms of Venus.”

|

| Jacob Grimm |

To understand the significance of the bell, we must again turn to the work of Jacob Grimm. He writes in Teutonic Mythology that, according to Germanic folklore, the heathen beings that survive into the Christian age have a great dislike of bell-ringing. Elves, dwarves, giants and witches hate to see churches built, because the sound of bells “disturbs their ancient privacy.” In his imagination, Tannhäuser hears a sound inimical to heathen beings. It is entirely fitting that this is what first sets him on the path out of the Venusberg. As a Minnesinger – a singer of songs – it also makes complete sense that a sound would resonate so deeply and meaningfully within his spirit.

Wagner again hints at the illusory nature of what we – through the mediation of Tannhäuser himself – are seeing and hearing. In the Bacchanale music, there is a striking passage for tambourine, triangle and cymbals. Was this what Tannhäuser heard in his dream-state and mistook for the sound of church bells? Throughout the opera, we watch Tannhäuser vacillate between desires for physical pleasure and spiritual love. The idea that the mishearing of heathen percussion as Christian bell would be the impetus for the drama fits well within Wagner’s schemata.

Given Tannhäuser’s confusion, it is noteworthy that most of what he longs for in this first dialogue is not overtly Christian. Between the imagined bells at the beginning of the scene and the naming of the Virgin Mary at the end, Tannhäuser yearns for sun, stars, grass, birds, spring, summer, woodlands, skies, meadows, pain and death. Everything he lists is part of the natural world, not Christian civilization.

|

| Tannhäuser (Robert Gambill) and Venus (Petra Lang) San Diego Opera (2008) |

While we may understand how the opera reflects Wagner’s own internal conflicts, we have yet to address the source for the debate between the poet and the goddess of the opera. The roots of the scene can be traced back to a four-stanza poem that appears under the name “Der tanuser” in the surviving medieval manuscript – a poem that is strikingly different in subject and tone from the other works attributed to the historical Minnesinger.

Here, instead of addressing a courtly audience and extolling the pleasures of country girls, he addresses God in the form of the “penitent song” and begs forgiveness for the sins of his youth: “I’ve spent my life in sinfulness and never been repentant, as I should. Thy suffering and divinity will surely give me aid that I may break my bonds and leave this life of sin, and make amends for all at last.”

Other late poems suggest that Tannhäuser experienced financial hardship after his jubilant youth due to his inability to secure a wealthy patron after the death of his original sponsor. It is most likely the contrast between the celebration of pleasure in Tannhäuser’s earlier works and the solemn penitence in this later poem that inspired the medieval legend of Tannhäuser in the Venusberg.

|

| "Das Lied von dem Daneüser" (1850 edition) |

J.W. Thomas presents a convincing argument that the original ballad of the Tannhäuser-in-the-Venusberg legend was composed in the decade after the death of the historical Minnesinger and survived in various versions until the appearance in 1515 of “Das Lied von dem Danheüser,” the earliest printed version of the story. After an introductory stanza, the narrator of the Lied tells us that

Tannhäuser was a knight who soughtThe next thirteen stanzas comprise a dialogue between Tannhäuser and Venus in which the goddess makes varied attempts to convince the hero not to leave. The ballad is not unique in its placement of a historical Minnesinger in a fantastic situation; similar medieval compositions were written of other popular poets.

adventure everywhere,

he entered Venusberg to see

the lovely women there.

There are a myriad of theories regarding the connection between the historical poet and the subject of the ballad. For Wagnerians, the most enjoyable (if intellectually unsustainable) theory is surely the one proposed by Adalbert Rudolf in 1882. According to Herr Rudolf, Tannhäuser was originally Wotanhäuser, a knight who abandoned Christianity, returned to heathenry, and was named for the Holy Mountain of Wotan – in which the god lived with his wife Freya, of course.

A less fantastic theory suggests that Tannhäuser was attached to the legend because of the nature of his poetic work. J.W. Thomas writes that the poems “portray a man who demands a joyous affirmation of life, who describes merry dances, who tells of his enjoyment of love’s delights, and all in all reveals a livelier sensuousness than do his contemporaries – who, however, in later songs, laments his fate and blames himself for his grievous situation.” The character of the historical Tannhäuser – at least as presented in his poems, which are all we truly have – made him a prime candidate to be slotted into a medieval Christian version of the traditional “into the mountain” narrative.

|

| Barbarossa with beard and ravens inside the mountain |

Grimm’s Teutonic Mythology has a long section on the Germanic idea of a mystic dweller inside a mountain. Notable in the list of heroes who were believed to live on inside rocky cliffs were Frederick Barbarossa and Siegfried; Wagner began an opera about the first and completed several about the second. Grimm suggests that, according to folk belief, the ancient heathen divinities lived on in wild places: “the pagan deities are represented as still beautiful, rich, powerful and benevolent, but as outcast and unblest, and only on the hardest terms can they be released from the doom pronounced upon them.” In the Tannhäuser ballad, Venus maybe be beautiful, but she is not quite benevolent. The Christian doom that damns her also extends to the knight in her service.

The German writer Heinrich Heine addresses these issues in Elementargeister (“Elemental Spirits”). This 1837 essay deals with the Tannhäuser legend and focuses on folklore ideas of pagan gods retreating from the onslaught of Christianity to resist medieval mores of guilt and self-denial from their underground fastnesses. This was clearly a concept that appealed to Wagner, whether he would admit to being influenced by the ideas of a Jewish author or not.

To be continued in Part Two.

Es fascinante la historia de esta opera de Wagner gracias por publicarla.

ReplyDelete